|

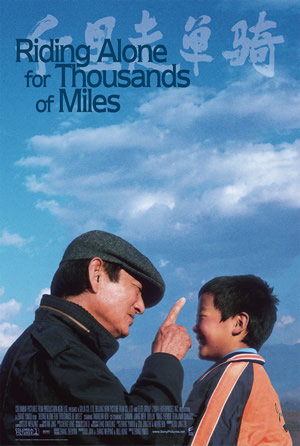

Genre:

Drama

Director: Zhang Yimou

Starring: Takakura Ken, Terajima Shinobu,

Nakai Kiichi

RunTime: 1 hr 47 mins

Released By: Columbia TriStar

Rating: PG

Opening

Day: 25 May 2006 (Opens in Singapore exclusively

at the Picturehouse)

Synopsis

:

For

the first time in many years, TAKATA Gou-ichi (TAKAKURA Ken)

takes the bullet train to Tokyo from the quiet fisherman’s

village where he lives on the northwest coast of Japan. His

daughter-in-law, Rie (TERAJIMA Shinobu) had telephoned to

tell him that his son, Ken-ichi (NAKAI Kiichi) is seriously

ill, and asking for his father.

But when

he arrives in the city, Takata finds that Rie was not entirely

truthful: Ken-ichi has been hospitalized, but after years

of painful estrangement, he still refuses to see Takata. Crushed,

the old man quietly slips out of the hospital, but not before

Rie gives him a videotape to watch. What Takata sees on the

tape, Rie hopes, will help him get to know his son again.

Takata

plays the tape and learns that Ken-ichi is studying a form

of Chinese exorcising drama that dates back more than a thousand

years. Ken-ichi had traveled all the way to Yunnan Province

in Southern China to see the famous actor LI Jiamin perform,

but the actor was ill and unable to sing. Li promised to sing

the legendary song ‘Riding Alone for Thousands of Miles’

from the literary classic, ‘Romance of the Three Kingdoms’

for Ken-ichi if he returns to Yunnan the following year.

Hoping

to bridge the gap between himself and his son, Takata decides

to find Li Jiamin and videotape his performance for the dying

Ken-ichi. As the old man begins an odyssey into the heart

of China, he encounters a number of strangers who colour his

journey -- from well-meaning translators who guide him through

China’s idiosyncrasies, to prison wardens anxious to

promote Chinese culture abroad, to a young runaway with a

complicated father-son relationship of his own.

What

Takata discovers on his journey is kindness… and a sense

of family he thought he had lost long ago.

Movie

Review:

Sometimes, when a director has achieved a certain level of

success, his aesthetic spark and cinematic acumen degenerate

into the kind of overindulgence that betrays the filmmaker’s

obsession with stringing together another hit. With the triumphs

of “Hero” and “House of Flying Daggers”

tucked safely in his back pocket, the onus was on Zhang Yimou

to produce another masterpiece. That he has done with “Riding

Alone for Thousands of Miles,” but more worthy of mention

is how he did it – by committing to a small-budget,

focusing on a heartfelt story and doing just what he does

best, directing.

What

is most striking about “Riding Alone for Thousands of

Miles” is it is such a simple film, so simple and accessible

that it’s almost offensive to brand it as “arthouse”

- a term nearly synonymous with “lofty” or “unfathomable”.

Simple but not without depth, the richness of character and

story as well as the masterful treatment of beautiful themes

in the film is truly testament of director Zhang Yimou’s

every professional acclaim. More than a story about an estranged

pair of father and son, “Riding…” additionally

revolves around the theme of expressing and understanding

feelings, the distinct awkwardness of which perhaps more resonant

and poignant in the Asian context. Filming largely in the

sprawling landscape of Yunnan, the film also explores Chinese

culture and customs, touches on communication and translation

and, among all these, still finds time to be surprisingly

comical. It is an undoubtedly enormous task, but trust Zhang

to pull it off with seeming composure and ease. What results

is a fluid and deceptively simple film: if a word could sum

up Zhang’s work, it would be ‘harmony.’

Takakura

Ken plays Takata Gou-ichi, a reclusive fisherman living peacefully

in the northwest coast of Japan. Upon receiving news from

his daughter-in-law Rie (Terajima Shinobu) of his son Ken-ichi’s

(Nakai Kiichi) hospitalization, he travels to Tokyo under

the false impression that his estranged son has requested

to see him. Rie was the one who’d invited him. The scene

of Takata shuffling his feet outside the hospital ward, overhearing

his son refuse to see him, is among the most visceral in a

film packed with quiet emotional punches. It is a straightforward

long shot of Takakura Ken that immediately conveys loneliness,

the sting of rejection, the unknown hurt driving father and

son apart and sadness. Sadness of knowing nothing has changed,

sadness of having harboured naïve hopes that things might

have changed. The absence of a confrontation between Ken-ichi

and Takata is, to me, intensely Asian. Not to mention, it

is far more effective by omitting shots of the seriously ill

Ken-ichi. Indeed, throughout the film, what is left unseen

and unsaid consistently has far more significance and emotional

weight than what is visible and audible.

Before

Takata leaves Tokyo for home, Rie hands him a tape of Ken-ichi’s

solitary trip to Yunnan a year ago, when he had missed the

chance to hear the famous actor Li Jiamin perform the song

‘Riding Alone for Thousands of Miles’. After watching

the tape, Takata learns that Li had promised to perform for

Ken-ichi if he returned a year later and so spontaneously

decides to leave for China to track down Li and obtain the

reel his now dying son had failed to. This might come across

as an absurd stretch of storyline but be patient, and the

film will persuade you that if you were Takata, you would

have done the same. Watch out for the ironically amusing scene

where Takata pleads for help from the Chinese officials who

are the only ones who can help him find Li. It is a masterpiece

of a scene, once again deceptively simple in conception and

construction. Suffice to say it involves Takata speaking from

a pre-recorded video as his guileless local guide translates

– you wouldn’t (and shouldn’t) miss it.

To

say that Takakura Ken is superb in his role would be an understatement.

There is a palpable connection between Takakura, Zhang and

the film that is indispensable to the success of “Riding…”.

Moreover, Zhang’s decision to employ first-time actors

for most of the native Chinese roles was a risk that paid

off handsomely. As Takata slowly progresses in his search

for Li, he encounters countless locals, each character as

vibrant as the next and all overwhelmingly, selflessly helpful.

There’s a feeling as you leave the theatre that you’ve

actually met all these people for they are so genuine the

film could as easily have been a documentary.

One

particular character that stands out is Takata’s guide,

Qiu Lin, who translates in a mixture of English and Japanese,

both of which confound Takata completely to the audience’s

amusement. Regardless, Qiu is devastatingly sincere –

before he begins to translate the video, he cheerily pipes,

“I’ve rehearsed for hours,” as though it

were his duty to do so. Such intensity is a common stereotype

of the Chinese and the film definitely milks it but I agree

with the filmmakers on this call; it is almost a Chinese (and

indeed, Asian) prerogative to be earnestly fraternal and passionately

loud, more often than not over a charming feast. At a farewell

meal thrown for Takata in a village where he’d received

help, the stoic man marvels at the manner with which he has

been embraced by these strangers and finally immerses himself

– in life, in emotions and in relationships. It is there

in the little village miles away from Tokyo that he begins

to bridge the gap between Ken-ichi and himself.

There

is also a lyrical parallel to be drawn between the two men

as it is assumed that Takata sees what Ken-ichi must have

one year ago. As he is taking in the scenic mountains of Yunnan,

Takata narrates that he finally understands why his equally

introverted son loved visiting China alone: it gave him an

excuse to withdraw. Hence for father and son their deepest

insecurities are the same; the lonely valleys reassure them

in the same way – it’s better to feel like an

outsider in a strange country than in your own home. But Takata

goes one step further than his son and gains self-revelation

when he decides to help Li to find his own estranged son.

When Takata finally accepts Li Jiamin’s request to sing

for him, recording the performance is no longer for Ken-ichi’s

purposes or Takata’s own but completely for Li. He understands

that Li needs to sing for him because it’s the only

thing he can do to commensurately repay Takata. The old Takata

would not have stayed. The new Takata listens with his heart.

The

film is filled with such scenes, each exquisitely concocted

to convey every possible message of culture, relationship

and communication, then topped off with a dose of lighthearted

humour. Every shot is so rich that the film is simply unending

layers of the filmmakers’ toil and thought, sewn together

seamlessly by Zhang, who manages to imbue every second of

“Riding…” with his commanding direction.

Yet there is no hint – not even a whisper – of

over-production on Zhang’s part, his directing work

in “Riding…” is the epitome of restraint

and grace. He is so attuned to his vision that he does exactly

what’s needed, nothing more or less, and he does it

all with natural, breathtaking brilliance. Some people are

just born with it.

Movie

Rating:

(Riding

Alone for Thousands of Miles” is like a rippling effect

– at the heart is direction so infectious that the film

forms concentrically and gently caresses you like a pulse.

You *have* to see it to understand)

Review

by Angeline Chui

|