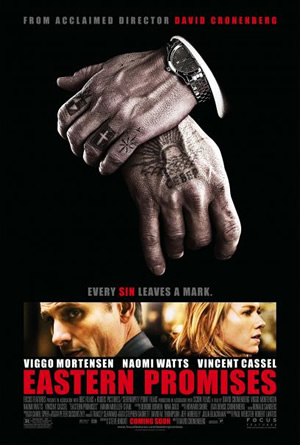

Genre:

Thriller

Director: David Cronenberg

Cast: Viggo Mortensen, Naomi Watts, Vincent

Cassel, Armin Mueller-Stahl, Sinead Cusack, Donald Sumpter,

Jerzy Skolimowski

RunTime:

1 hr 50 mins

Released By: Shaw

Rating: M18

(Violence & Nudity)

Official Website: www.focusfeatures.com/easternpromises/

Opening Day: 3 January 2008

Synopsis:

Eastern Promises follows the mysterious and ruthless Nikolai

(Viggo Mortensen), who is tied to one of London's most notorious

organized crime families. His carefully maintained existence

is jarred when he crosses paths with Anna (Naomi Watts), an

innocent midwife trying to right a wrong, who accidentally

uncovers potential evidence again the family. Now Nikolai

must put into motion a harrowing chain of murder, deceit,

and retribution.

Movie Review:

When Nikolai (Viggo Mortensen) stands bare and initiated in

front of an unsavoury conclave of old men, his heavily tattooed

physique and scarred form disclose a imperative of duty and

an identity given in a city that holds none. The arcane nature

of Nikolai’s shadowy being brings about lines of honour

and undead servitude, a testimony of corruption through an

examination of physical transformations and the concept of

the self. The disfigurement of the frame also wretches the

spirit as David Cronenberg typically queries the relationship

between the body and soul. The question emerges: Who are these

men that feed on others? The vampiric cabal feasts on the

city’s death and its overwhelming despair, and only

those who have truly revoked humanity are inducted into their

sphere.

In

Cronenberg’s masterful “Eastern Promises”,

London is presented as a teeming hive of ethnic and ethical

tensions fueled by the cultural isolation of its displaced

immigrants. The turmoil beneath its temperate exterior is

palpable; a rumple felt only when a corpse is thrown into

the Thames as another surfaces, bringing with it a cache of

buried secrets. Russian blood is spilt simultaneously, the

last of which brings a dead teenage prostitute’s newborn

to midwife Anna’s (Naomi Watts) care as an intermittent

narration from the dead girl’s diary reveals a quaint

concept of sympathy that is only shown to only those that

deserve it.

From

hamburgers to caviar, Cronenberg crosses the same themes and

inquiries that he explored in “A History of Violence”,

intriguingly casting the stupendously virile Mortensen and

then incisively inflicting the same sorrow on the fractured

personalities and tortured moralities of his taciturn characters.

Slick and severe with a lurking mood of insinuating hostility

behind every corner, the one thing scarier than the presence

of evil is the absence of anything at all. The cold void left

behind in all-American family man’s Tom Wells as he

finally sat down at the dinner table is transported to the

grunge of inner city London, where Nikolai waits as a driver

(among other things) outside a tranquil Trans-Siberian restaurant,

a swanky shroud for its venal cults within. With a wry and

cynical sense of humour, Nikolai is deadly aware of the world

he operates in and he traverses it with a brutal intelligence.

Mortensen’s angular features and sturdy physicality

once again serve to accentuate these moral ambiguities and

add to the edge of his fascinating character in a completely

ravishing performance of technique and control.

Cronenberg

retains the clinically intense sensibilities of violence and

its acceptance from his previous film and ups the ante here

with even more memorable set pieces. Injecting the incongruent

melodrama of the screenplay from Steven Knight (writer of

another London-based émigré themed, “Dirty

Pretty Things”) with fluidity and verve, Cronenberg

puts physical vulnerabilities before emotional ones. Even

through the flourishes of explicit violence, he maintains

an aloof velocity of motion and precision that while rigidly

formal in its explosive rage, also surveys its images with

ambivalent guile. He takes the mobster genre and removes the

romanticism of unspoken brotherhood and strained lines of

its cryptic inner world by focusing on its various characters’

seemingly stoic responses to their environment and their own

perpetual criminality by constantly stripping away to reveal

more instances of truth.

The

father-son combo that rounds off Nikolai’s nucleus in

the vory v zakone (the Russian mafia) is the uncompromising

godfather, Semyon (a strong performance by Armin Mueller-Stahl)

who controls his ‘family’ with fear rather than

respect, and Semyon’s volatile progeny Kirill (Vincent

Cassel). Both prominently entwined in its backstory of modern

flesh trafficking together with Watt’s underappreciated

tidal waves of guilt and complexities that relate to the newborn

and the untranslated document of suffering that binds them

together. But Nikolai emerges as Cronenberg’s sincerest

preoccupation, a study of a man guarded with surreptitious

anguish whose only reprieve from Cronenberg’s contemplation

of personal horror is a penultimate shot that is as blistering

a shot of familial guardianship as you are likely to find

anywhere in his oeuvre.

Movie Rating:

(Cronenberg pushes his themes further with a glorious brutality

of flesh and mind)

Review by Justin Deimen

|